Introduction

This brief grammar sketch is meant to give a short introduction into Rohingya grammar and is intended for non-linguists. We have intentionally tried to avoid being too technical and sought to use terminology understood by a wider audience. A more formal and in-depth analysis of Rohingya grammar will be published later.

Our analysis of the Rohingya language has been a work in progress for several years and is still ongoing. Per request from expats, working with Rohingya refugees, we have decided to publish this brief grammar earlier than intended. Hence, expect future revisions.

Rohingya (aka.Ruáinga, Rohinja, Rohinga) is a language spoken in the northern Rakhine state of Myanmar and is part of the Bengali-Assamese branch of Eastern Indo-Aryan language family. It is closely related to the Chittagonian language spoken in neighboring Bangladesh.

It is difficult to ascertain the exact number of Rohingya speakers; however, it is estimated that there are probably around 2 – 3 million Rohingyas spread around the world, most of whom are refugees or illegal immigrants in neighboring countries.

Orthography

Orthography is a system for representing a language in written form. Often, people will think of only symbols and letters when they think of orthography. A solid phonological analysis is one of the foundations for developing a good orthography. It involves identifying distinct phonemes (contrasting sounds), as well as decisions concerning when to separate words or combine them, and so on.

Sounds and example words

In any language, native speakers will utter a lot more sounds (phones) than the contrasting sounds (phonemes) which serve to separate words from one another, and Rohingya is no exception. In this section we will look at all the speech sounds in the Rohingya language, and group sounds with their sound variations (allophones) into a list of phonemes that should be represented in the orthography, starting with vowels and then consonants.

Vowels (oral, nasalized and stressed)

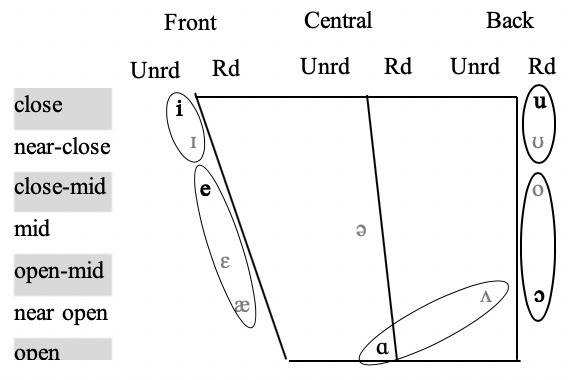

The diagram below shows all the phonetic vowel sounds, as well as the phonemic ones in Rohingya. The vowel sounds are grouped into phonemes (distinguishing sounds, written in bold) with allophones (written in grey).

| Linguistic terms | Explanation |

|---|---|

| phones | any speech sound and is represented between brackets by convention. |

| phonemes | the contrastive sounds that serve to distinguish words from each other in meaning, and represented between slashes by convention. |

| allophones | variation of speech sounds |

| phonology | the study and analysis of speech sound patterns in a language |

It is not necessary to represent all 12 vowel sounds in the orthography. The phonemic analysis of vowel sounds in the language shows us that there are only 5 base vowel sounds that are contrastive (in addition to nasalized, lengthened, and stressed vowels), as such can be represented in the writing system.

Rohingya also makes a distinction between oral vowels (non-nasalized) and nasalized vowels, that is, nasalization on a vowel makes a difference in the meaning of words. Consider the following examples, in which the only phonetically different segment is nasalization on the vowel:

| (1) | ãi "I (1SG)" | ai "come" |

| ḍõr "big" | ḍor "fear" |

|

| tũi "you (2SG, honorific)" | tui "you (2SG, non-honorific/when addressing younger people )" |

|

| ũṭ "lips" | uṭ "Stand up!" |

| Rohingya Oral Vowels | ||

|---|---|---|

| i | u | |

| e | o | |

| a | ||

| Rohingya Nasalized Vowels | ||

|---|---|---|

| ĩ | ũ | |

| ẽ | õ | |

| ã | ||

Thus, we can conclude that Rohingya has 10 phonemic vowel sounds that need representation in the Rohingya alphabet. The list of vowels in the language is provided with their IPA symbols, pronunciation guide and example words in Rohingya in the table below.

| Letter | IPA | Pronunciation guide | Examples in Rohingya |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /ɑ/ | pronounced openly as a in the Italian ‘amore’ | anḍa "egg" asman "sky" |

| Ã ã | /ɑ̃/ | nasalized pronunciation of /ɑ/ | ãi "I (1SG)" ãra "we (1PL)" |

| E e | /e/ | as e in ‘pet’. | enaš "pineapple" tel "oil" |

| Ẽ ẽ | /ẽ/ | nasalized pronunciation of /e/ | fẽsa "owl" kẽs "body hair" |

| I i | /i/ | as ee in ‘sheep’. | isamas "shrimp" |

| Ĩ ĩ | /ĩ/ | nasalized pronunciation of /i/ | gĩyu "grain, seed" |

| O o | /ɔ/ | pronounced openly as oo in ‘door’. | ošuk "sick" |

| Õ õ | /ɔ̃/ | nasalized pronunciation of /ɔ/. | õṛi "ring" õl "finger" ḍõr "big" |

| U u | /u/ | as oo in ‘noon’. | usol "high" |

| Ũ ũ | /ũ/ | Nasalized pronunciation of /u/. | ũṭ "lips" kũir "dog" |

Vowels can also be lengthened in Rohingya. Lengthened or long vowels are marked by doubling the vowel symbol, as in the following examples:

| Rohingya | English |

|---|---|

| iin | "these" |

| hoor | "clothes" |

A few words in Rohingya receive stress on the vowel. Where there is a clear distinction in meaning, the acute accent can be added on the vowel that receives the stress, as in bai “through” vs. bái “brother” and gor- “do” vs. gór “house.” Otherwise, context will determine the meaning of words that have stressed vowels.

“A diphthong … is a sequence of two vowels that functions as a single sound” (Hayes, 2008). In Rohingya, we find a number of diphthongs, as shown in the table below. Common for all these diphthongs is that they end with a high vowel (e.g. [i] and [u]).

| Letter | IPA | Pronunciation guide | Examples in Rohingya |

|---|---|---|---|

| ai | /ɑ͡i/ | this diphthong is pronounced as in "bye" | bái "brother" fuwain "child" |

| ei | /e͡i/ | pronounced as in "day" | beil "sun" leikke "(have) written" |

| oi | /ɔ͡i/ | as in "boy", but less emphasized | boin "sister" |

| ou | /ɔ͡u/ | as in "home", but less emphasized | bou "wife" |

| ui | /u͡i/ | close to Spanish "muy" | dui "two" |

| ãi | /ã͡i/ | as a nasalized version of the pronoun "I" | ãi "I (1SG)" |

| ũi | /ũ͡i/ | close to Spanish "muy", but nasalized | tũi"you (2SG, honorific)" |

In Rohingya, there is also another type of vowel combinations, called glides. These include /ua/, /ũa/, /ia/, /ie/, /io/, /iu/, /ĩu/, /uo/, and /ue/, where the high vowels [i] and [u] come before the prominent vowels. In this type of sequence, a consonant (/j/ or /w/) is inserted. This is in accordance with the Rohingya syllable structure rules, which state that there is no vowel cluster in word internal positions, or that all syllables in Rohingya must have an onset (syllable- initial consonant), except in word initial positions. The vowel glides /ua/, /ũa/, /ia/, /ie/, /io/, /iu/, /ĩu/, /uo/, and /ue/ are, then, written as follows:

| Vowel glides | How they should be written | Example words |

|---|---|---|

| /ua/ | -uwa- | fuwa "child" duwa "prayer" januwar "animal" |

| /ũa/ | -ũwa- | tũwara "you (2PL)" |

| /ia/ | -iya- | ṭiya "money" iyan "this" |

| /ie/ | -iye- | diye "gave" giye "went" |

| /io/ | -iyo- | giyos "(have) gone" niyom "normal" |

| /iu/ | -iyu- | miyula "cloud, sky" diyum "will give" |

| /ĩu/ | -ĩyu- | gĩyu "grain, seed" |

| /uo/ | -uwo- | uwore "on, upon" šuwor "pig, swine" |

| /ue/ | -uwe- | bouwe "wife (AG)" |

Consonants

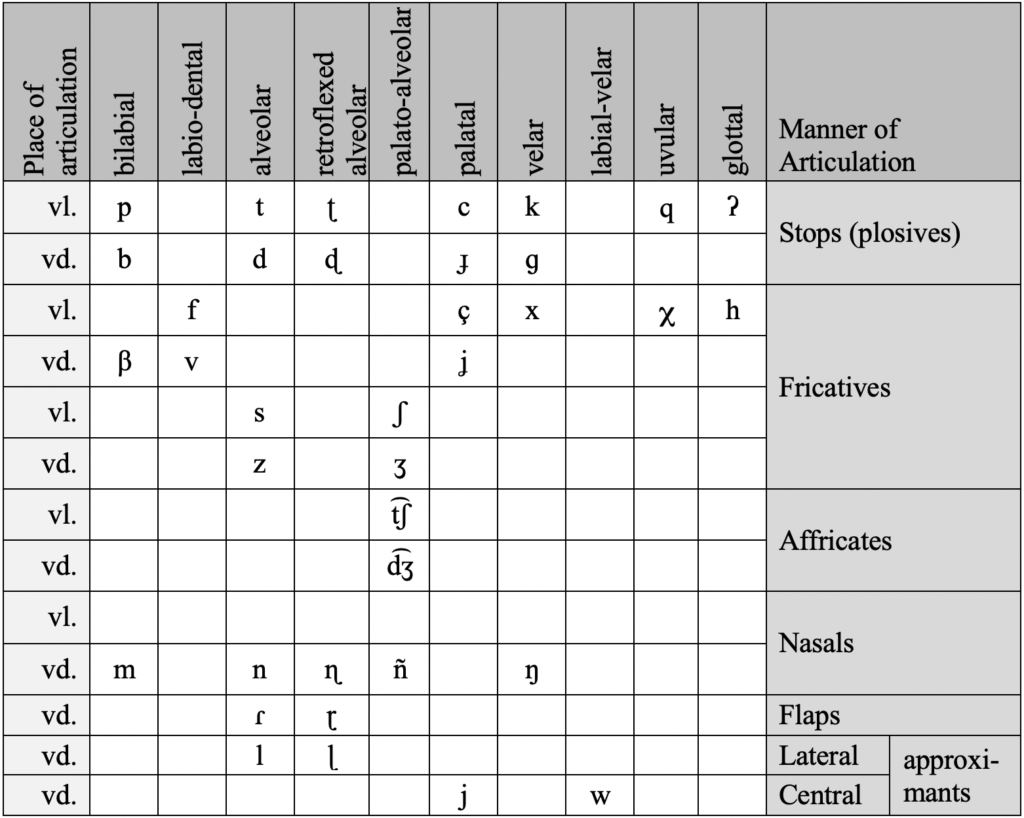

Following is an IPA[1] chart for all the consonant sounds a native Rohingya speaker makes, not a phoneme chart (the underlying sounds as they are subconsciously organized in the mind of the native speaker).

[1] IPA stands for International Phonetic Alphabet. Ref. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Phonetic_Alphabet

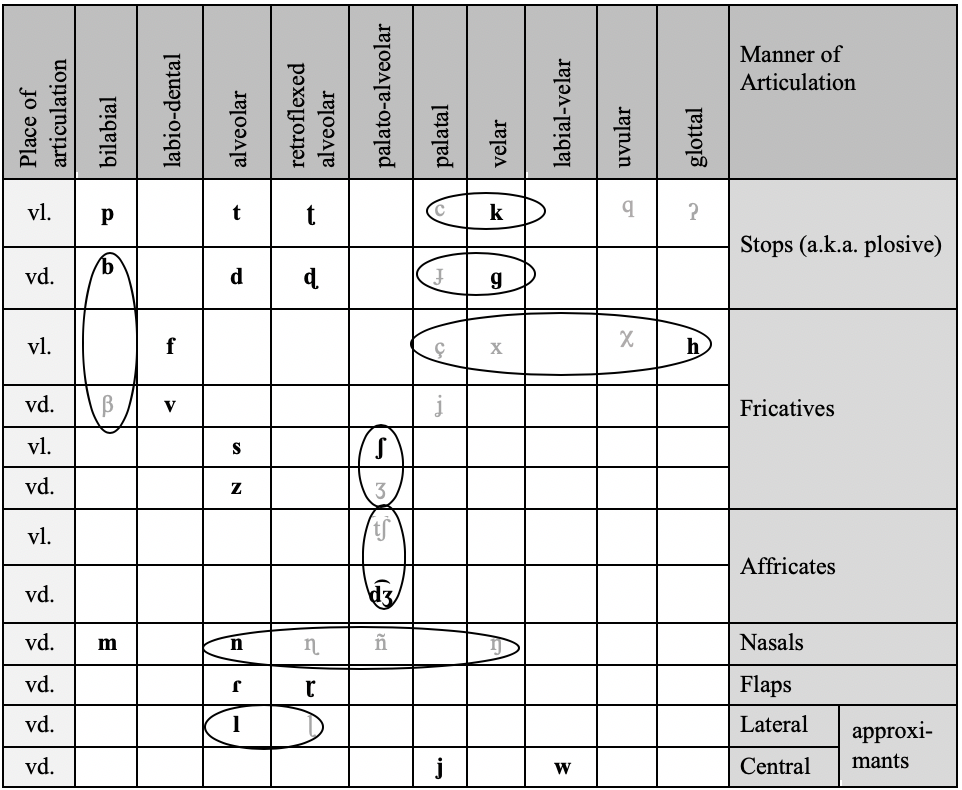

If all the sounds in the phone chart above were to make it to the Rohingya alphabet, it would have 37 consonant characters. However, all these sounds behave in a certain, predictable way that only a subset of these sounds (phonemes) needs to be represented in the orthography. These phonemes consist of one or more allophones.

The following chart for inventory of consonant phonemes describes which phones are grouped together and belong to which phonemes. The phonemic representation of these allophones is written in bold.

In the phoneme chart above, we can see that Rohingya has 22 phonemic consonants represented in the writing system. The list of consonants in the language is provided with their IPA symbols, pronunciation guide and example words in Rohingya in the table below.

| Letter | IPA | Pronunciation guide | Examples in Rohingya |

|---|---|---|---|

| B b | /b/ | as b in ‘boy’ | bat "cooked rice" bayon "eggplant" |

| D d | /d/ | as d in ‘dog’ | dan "rice plant" |

| Ḍ ḍ | /ɖ/ | This is a retroflexed sound, pronounced with the underside of the tongue curled up just behind the alveolar ridge. | ḍõr "big" anḍa "egg" |

| F f | /f/ | as f in ‘fun'. | fuwa "child" fani "water" |

| G g | /ɡ/ | as g in ‘go’. | gór "house" gá "body" gula "fruit" gas "tree" |

| H h | /h/ | as h in ‘home’. | hana "food" hat "hand" hosara "dust" |

| I i | /i/ | as ee in ‘sheep’. | isamas "shrimp" |

| J j | /d͡ʒ/ | as j in ‘jam’. | januwar "animal" |

| K k | /k/ | pronounced as k in ‘car’ (without much aspiration). | kitab "book" kura "chicken" |

| L l | /l/ | as l in ‘lap’, not as l in ‘pal’. | lal "red" lamba "tall, high" |

| M m | /m/ | as m in ‘man’ | manuš "man" miyula "cloud" mas "fish" |

| N n | /n/ | as n in ‘name’. | nun "salt" nak "nose" |

| P p | /p/ | pronounced as p in ‘pet’ (without much aspiration). | in loan words or foreign words |

| R r | /ɾ/ | as the flap in r of Italian ‘primo’. | ruṭi "bread" rari "widow" |

| Ṛ ṛ | /ɽ/ | Retroflexed sound (a flap), pronounced with the underside of the tongue just behind the alveolar ridge. | ṛaṭi "famine" |

| S s | /s/ | as s in ‘same’. | sini "sugar" sul "hair" |

| Š š | /ʃ/ | as sh in ‘ship’. | šõṛo "small" šohor "city" |

| T t | /t/ | This is a dental sound, pronounced with the tip of the tongue touching upper teeth, as the t in the French word ‘tres’ for ‘very.’ | tormus "watermelon" |

| Ṭ ṭ | /ʈ/ | This is the voiceless equivalent of ḍ. For pronunciation tip, see ḍ. | ṭayon "tomato" ṭam "a type of mango" ṭoka "to deceive" |

| V v | /v/ | This voiced fricative is found only in foreign names or borrowed words. | |

| W w | /w/ | as w in ‘wax’ | wada "promise" |

| Y y | /j/ | as y in ‘year’ | |

| Z z | /z/ | as z in ‘zebra’ | zaga "place" zamai "husband" zil "tongue" zuta "shoes" |

Many of these consonants can be lengthened, in which case it is marked by doubling the symbol. Example words with double consonants are provided below:

| Rohingya | English |

|---|---|

| aijja | "today" |

| biššaš | "faith" |

| beggun | "all" |

| ḍaikke | "(he) called" |

| edde | "and" |

| fisottu | "behind" |

| hazinna | "evening" |

| hailla | "tomorrow" |

| hoišša | "young" |

| mattul | "hammer" |

| mikka | "towards" |

Different kinds of words

As in any language, Rohingya has a group of words, which are borrowed from neighboring languages, including English, and have been so adapted into the phonological system of the language that most native speakers will not think twice about the origin of these words and will think of them as Rohingya words. Here are only few examples:

| Loan words | |

|---|---|

| Rohingya | Gloss |

| bala | "good, well, fine" |

| bakšu | "box" |

| boi | "book" |

| doroza, duwar | "door" |

| gološ | "glass" |

| gari | "car" |

| kitab | "book" |

| maštor | "master, teacher" |

| nas | "nurse" |

| ṭebil | "table" |

| ṭon | "town" |

| ziyol | "jail, prison" |

Clause Structure

Intransitive Clause

Intransitive clause is a clause in which the verb has only one argument, namely the subject argument (S). Verbs (V) in this type of clause do not require an object (O), as described in examples (2-5). These examples show the linguistic conventions, in which the first line is for data in the vernacular language, the second line for back translation and the third line for free translation of the language data.

| (2) | S | V |

| Moriyam | handil. | |

| Moriyam | wept. | |

| "Moriyam wept." | ||

| (4) | S | V |

| Hibaye | boišše. | |

| She | sat. | |

| "She sat." | ||

| (3) | S | V |

| Jakob | hãser. | |

| Jacob | laugh. | |

| "Jakob is laughing." | ||

| (5) | S | V |

| Ãi | dũrir. | |

| I | run-PROG. | |

| "I am running." | ||

Transitive Clause

Transitive clause is a clause in which the verb has two arguments, the subject and object. In example (6) the verb hair “eat” has the subject argument ãi “I” and the object argument hana “food.” In example (7) the verb dekkil “see” has the subject argument hite “he” and the object argument hibare “her.”

| (6) | S | O | V |

| Ãi | hana | hair. | |

| I | food | eat. | |

| "I'm eating food." | |||

| (7) | S | O | V |

| Hite | hibare | dekkil. | |

| He | her | saw. | |

| "He saw her." | |||

| (8) | S | O | V |

| Anware | kitabwa | fore. | |

| Anwar (ERG) | book | read. | |

| "Anwar read the book." | |||

Attributive Clause

An attributive clause describes a person or an object. Rohingya speakers may use linking verbs (copulas) oilde “be.pres” and aššilde “be.past” in this type of clause. It is also natural to omit the copula altogether, when it is in the present tense, as in example (12), in which case the complement will come at the end of the clause. In these examples, NP stands for noun phrase, COP stands for copula (a linking verb is another term for copula, used interchangeably) and ATP stands for attributive phrase.

| (9) | NP | COP | ATP | ||

| Ei | fúllwa | oilde | beši | šundor. | |

| this | flower | is | very | beautiful. | |

| "This flower is very beautiful." | |||||

| (10) | NP | COP | ATP |

| Hiba | oilde | salak. | |

| She | is | wise | |

| "She is wise." | |||

| (11) | Subject | COP | ATP |

| Hite | aššilde | lamba. | |

| He | was | tall | |

| "He was tall." | |||

| (12) | NP | ATP | ||

| Ei | fúllwa | beši | šundor. | |

| this | flower | very | beautiful. | |

| "This flower is very beautiful." | ||||

Equative Clause

An equative clause describes a feature (the title, position, profession or status of a person usually) of its subject in the clause. Like attributive clauses, an equative clause consists of the subject noun (noun phrase/pronoun), a linking verb/copula, and a complement, the element that is being equated with the subject. Note that in examples (15) and (16) the copula is dropped.

| (12) | Subject | COP | NP | ||

| Itara | aššilde | hibar | fuwain | okkol. | |

| These | were | her | child | PL | |

| "These were her children." | |||||

| (13) | NP | COP | NP | |

| Hibar | nam | oilde | Habiba. | |

| Her | name | is | Habiba | |

| "Her name is Habiba." | ||||

| (14) | NP | COP | NP | ||

| Hitar | ma | aššilde | ekzon | nas. | |

| His | mother | was | a | nurse | |

| "His mother was a nurse." | |||||

| (15) | NP | NP | ||

| Hitar | bou | ekzon | ḍakṭor | |

| His | wife | a | doctor | |

| "His wife is a doctor." | ||||

| (16) | NP | NP | |

| Ãr | nam | Anna. | |

| my | name | Anna | |

| "My name is Anna." | |||

Locative Clause

A locative clause gives information about the location of its subject in the clause. In Rohingya, a locative clause consists of a noun phrase, followed by an optional copula, and a locative phrase. Example (17) describes the clause with a copula, while example (18) shows that it is also natural to omit the copula.

| (17) | NP | COP | LOC | |||

| Lal | bakšuwa | oilde | hail | bakšur | munttu. | |

| red | box | is | green | box's | front | |

| "The red box is in front of the green box." | ||||||

| (18) | NP | LOC | |||

| Lal | bakšuwa | hail | bakšur | munttu. | |

| red | box | green | box's | front | |

| "The red box is in front of the green box." | |||||

Possessive Clause

The possessive clause describes the possession of a person or an object. In Rohingya possession can be expressed by the use of the verb ase “have.” The possessor is the subject of the clause or sentence and the possessed item occurs before the verb. The subject of the clause also takes the ablative case (for full noun inflection list, click here). Consider the following examples:

| (19) | Ãttu | tin | boin | ase. |

| I | three | sister | have | |

| "I have three sisters." | ||||

| (20) | Bobottu | šõṛo | bái | ase. |

| Bob | little | brother | have | |

| "Bob has a little brother." | ||||

Phrases

Phrases are a combination of words (constituents), which build up clauses. There are different types of phrases; noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and postpositional phrases (PostP).

Noun Phrase

Noun Phrase is a phrase in which the noun is the head. Besides the noun, the noun phrase can have modifiers. The modifiers are adjectives, numerals, and demonstratives. These modifiers precede their head nouns in Rohingya.

Noun Phrases with Adjective

A noun phrase with an adjective is a phrase in which the head noun is modified by an adjective. Like English, Rohingya adjectives function as descriptive modifiers in a noun phrase and occur before their head nouns. Grammatically, they do not take plural marking, noun classifiers, or possessors. Semantically, they describe or say something about the noun they modify, such as color, size, quality, shape or material. Consider the following examples:

| (21) | ADJ | HEAD |

| lal | bakšuwa | |

| red | box | |

| "the red box" | ||

| (22) | ADJ | HEAD |

| lamba | bái | |

| tall | brother | |

| "tall brother" | ||

| (23) | ADJ | HEAD |

| ḍõr | górgan | |

| big | house | |

| "the big house" | ||

If the adjective comes after the head noun, it is not a noun phrase anymore. It is now an attributive clause, with a noun phrase (NP) and an attributive phrase (ATP). Consider the following examples:

| (24) | NP | ATP |

| Bakšuwa | lal. | |

| box | red | |

| "The box is red." | ||

| (25) | NP | ATP |

| Górgan | ḍõr. | |

| house | big | |

| "The house is big." | ||

Noun Phrases with Adjective and Numerals

In a noun phrase with adjective and numerals the head noun is modified by both an adjective and a numeral. In example (24), the head noun is mas “fish” and is modified by the numeral tinnwa “three” and the ajdective ḍõr “big”. The following examples illustrate the basic constituent order for NPs, which is NUM ADJ HEAD. Consider the examples:

| (24) | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| tinnwa | ḍõr | mas | |

| three | big | fish | |

| "three big fish" | |||

| (25) | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| duizon | bukalo | fuwain | |

| two | hungry | child/boy | |

| "two hungry boys" | |||

| (26) | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| ekkan | boro | gór | |

| one | big | house | |

| "one big house" | |||

| (27) | uggwa | lal | holom |

| one | red | pen | |

| "one red pen" | |||

Noun Phrases with Adjective, Numerals and Demonstratives

There is another type of modifiers that can modify the head noun in a noun phrase, that is, demonstratives (this, that, these and those). Their position in the NP is always first, as described by the examples (27) and (28).

| (27) | DEM | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| ei | duizon | bukalo | fuwain | |

| these | two | hungry | boy | |

| "these two hungry boys" | ||||

| (28) | DEM | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| oi | tinnan | šundor | gór | |

| those | three | beautiful | house | |

| "those three beautiful houses" | ||||

Verb Phrase

In the verb phrase (VP), a verb is the head of the phrase. There are two types of VPs: 1) intransitive verb phrase, in which there is only one constituent, which is the verb, and 2) transitive verb phrase, in which there are more than one constituent, that is, the object NP. Traditional grammar uses terms such as direct and indirect object. See the section on intransitive and transitive clauses.

Postpositional Phrase

Postpositional phrase is an adpositional phrase in which a postposition is the head. Rohingya adpositions occur after their complement (usually combined with nouns or pronouns), and are called postpositions. Because Rohingya postpositions are originally derived from nouns, the Genitive case suffix is often used to link the postposition with the nominal element. Note that in fast speech it is also natural to drop the Genitive case on the noun, as in examples (29), in which both constructions are correct.

| Rohingya postpositions | Gloss | with pronoun complement | with noun complement |

|---|---|---|---|

| baire | "out, outside" | góror baire "outside the house" |

|

| bifokke | "against" | tũwar bifokke "against you" | |

| butore | "in, inside" | tũwar butore "in you" | góror butore "inside the house" |

| ḍake | "beside, on the side of, near" | ãrar ḍake "near us" | šohoror ḍake "near city" |

| fisottu | "behind" | hitar fisottu "behind him" | gasor fisottu "behind tree" |

| fokke | "for" | hitarar fokke "for them" | |

| fũwatti | "with," | tũwar fũwatti "with you" | báiyor fũwatti "with brother" |

| hãse | "near" | hitar hãse "near him" | fuwar hãse "near child" |

| maze | "among, between" | ãrar maze "among us" | bakšuwar maze "between the boxes" |

| mikka | "towards" | ||

| munttu | "before, in front of" | hibar munttu "before her" | bafor munttu "in front of father" |

| nise | "under" | holomor nise "under pen" |

|

| sarme | "before, in front of" | ãr sarme "before me" | fuwar sarme "in front of child" |

| tole | "under" | bakšur tole "under box" |

|

| uwore | "on, upon" | ãr uwore "on me" | matar uwore "on the head" |

| uzu | "to, toward" | tũwarar uzu "toward you" | farar uzu "toward village" |

| Noun-GEN Postpositions | Noun Postpositions | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (29) | góror baire | gór baire | "outside the house" |

| šohoror ḍake | šohor ḍake | "near city" | |

| gasor fisottu | gas fisottu | "behind tree" | |

| bái(y)or fũwatti | bái fũwatti | "with brother" | |

| fuwar hãse | fuwa hãse | "near child" | |

| holomor nise | holom nise | "under pen" |

Examples of how postpositions are used in a clause are provided below:

| (30) | Hitar | gór | hitarar | góror | hãse. |

| his | house | their | house's | near | |

| "His house is near their house." | |||||

| (31) | Lal | bakšuwa | hail | bakšuwar | fisottu. |

| red | box | green | box's | behind | |

| "The red box is behind the green box." | |||||

Nouns

Nouns express one of the most time-stable concepts, i.e., objects, such as trees, plants, stones and body parts. Prototypical nouns in Rohingya are words that refer to people, places, things (concrete), ideas and concepts (abstract), and can be characterized as having the following morphosyntactic properties; 1) number marking (singular and plural), 2) noun classifier marking, 3) case marking, and 4) possession.

The types of nouns found in Rohingya are concrete nouns, abstract nouns, and proper nouns.

Concrete and abstract nouns

Concrete nouns are words that refer to what is viewed as material entity, while abstract nouns are words that refer to nonmaterial entities, such as ideas, thoughts or concepts. Grammatically, they are marked for plurality, noun class, case, and possession. Most Rohingya nouns, when they are in the plural, take okkol when the items are not specified / indefinite. Note that when these nouns occur with numerals, it is natural to drop the plural marking okkol, as in example (32). See the section on Rohingya noun class system and noun inflection.

| Rohingya nouns (Indefinite and singular) | Gloss | Rohingya nouns (Indefinite and plural) | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (32) | bilai | "cat" | bilai okkol | "cats" |

| gór | "house" | gór okkol | "houses" | |

| hat | "hand" | hat okkol | "hands" | |

| kũir | "dog" | kũir okkol | "dogs" | |

| manuš | "man" | manuš okkol | "men" | |

| õl | "finger" | õl okkol | "fingers" | |

| šuwor | "pig" | šuwor okkol | "pigs" |

| (33) | gór | "house" | tinnan gór | "three house(s)" |

| hat | "hand" | duiyan hat | "two hand(s)" | |

| manuš | "man" | barozon manuš | "twelve man" | |

| mas | "fish" | tinnwa manuš | "three fish" |

Following are some examples of Rohingya abstract nouns:

| Proper nouns | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|

| (34) | ador, muhabbot | "love" |

| azadi | "liberty, freedom" | |

| gušša | "anger" | |

| insaf | "justice, righteousness" | |

| soyi | "truth" |

Proper Nouns

Proper nouns are nouns that are the names of persons, places, and objects. Following the general writing convention, the first letter of proper nouns are always capitalized.

| Proper nouns | Incorrect | |

|---|---|---|

| (35) | Anwar | |

| Arakan | ||

| Bodolu | ||

| Ḍaka | ||

| England | ||

| Moriyam | ||

| Salim |

Noun classes

A noun class system is a grammatical system that some languages use to group all nouns into a smallish number of classes.

Dixon 2010

Rohingya has a noun class system which involves the presence of classifiers as suffixes (article-like determiners), which are attached directly on almost all nouns, except proper nouns and non-referential nouns, such as day and year, to express the class of the noun. Rohingya noun classifiers are suffixes that group nouns in two classes on the basis of shared common features, such as animacy. They are also obligatory when numerals, quantifiers, and demonstrative pronouns occur. Rohingya has the following two noun classes:

- Noun Class One (NC1): When a noun refers to everything animate, including humans, animals, plants, and some objects which are manipulated by humans, such as book, pen, glass, etc .

- Noun Class Two (NC2): Everything else that is inanimate, and abstract nouns, such as justice, freedom, etc.

The following table displays and exemplifies the noun classifiers in context and definiteness; definite (DEF) or indefinite (INDEF). The hyphen between the words, i.,e, manuš-š-wa, fúll-wa, gór-g-an indicates a morpheme break within a word, not a word break.

Linguistic terms

morpheme – the smallest meaningful unit

The English word cats consists of two

morphemes, the stem/bare form cat

and the suffix -s.

affix – a bound morpheme (prefix or suffix)

suffix – an affix attached to the end of a stem.

For the Rohingya word górgan, -an is

the suffix, which expresses the noun

class in the singular for NC2.

| Noun classes | Examples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | PL | SG | PL | ||

| NC1 (-wa) | DEF | -wa | -un | manuš-š1-wa "the man" | manuš-š-un "the men" |

| fúl-l-wa "the flower" | fúl-l-un "the flowers" | ||||

| holom-m-wa "the pen" | holom-m-un "the pens" | ||||

| INDEF | ekzon2 / uggwa | okkol | ekzon manuš "a man" | manuš okkol "men / people" | |

| uggwa fúl "a flower" | fúl okkol "flowers" | ||||

| uggwa holom "a pen" | holom okkol "pens" | ||||

| NC2 (-an) | DEF | -an | -un | gór-g3-an "the house" | gór-g-un "the houses" |

| INDEF | ekkan | okkol | ekkan gór "a house" | gór okkol "houses" | |

NOTE 1: When the word stem ends with a consonant (except /r/), the suffixes -wa / -an / -un will lengthen the last consonant in the stem:

- manuš + -wa =>manuššwa

- fúl + -wa => fúllwa

- holom + -un => holommun

- gas + wa => gasswa

NOTE 2: Ekzon is used in the INDEF for humans and for counting humans, e.g., ekzon maštor “a/one teacher” and duizon manuš “two men.” Uggwa is used for everything else.

NOTE 3: When the word stem ends with a vowel or the consonant /r/, the suffixes -an and -un will insert /g/ between the noun stem and the suffix:

- gór + -an => górgan

- fara + un => faragun

When the suffix -wa comes after a noun stem that ends with the consonant /r/, the consonant /g/ will be inserted between the stem and the suffix:

- sair + wa => sairgwa

- bandor + wa => bandorgwa

However, when the suffix -wa comes after a stem that ends with a vowel, then there is no insertion:

- fuwa + wa => fuwawa

- goru + wa => goruwa

- bakšu + wa => bakšuwa

Note that non-referential nouns, such as time words, are unmarked for definiteness in both singular and plural, but takes the bare form of numbers for indefiniteness, e.g.: ek din “a/one day” and dui bosor “two year(s)”.

Plurality

All nouns in Rohingya in the indefinite, regardless of which noun class they belong to, take the same plural marker okkol, which is a free form, i.e., it occurs as a separate word, as shown in the noun class table above.

Noun Inflection

In Rohingya, nouns are inflected for case. Case is indicated by distinctive markers. These case markers are bound, in that they are attached to the noun they inflect. Rohingya has eight morphologically distinct cases, which are used in the following way in terms of their syntactic function in the clause:

| Cases | Case markers | Syntactic function in the clause |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutive (ABS) | bareform / unmarked | indicates the subject of the clause, indefinite and/or inanimate object, expressed by the bare form of the noun. |

| Ergative (ERG) | -e | marks the Subject of transitive clause, indicates the Agent of the action. |

| Genitive (GEN) | -r | indicates possession "of". |

| Dative (DAT) | -re | marks the Indirect Object of the clause. |

| Ablative (ABL) | -ttu | indicates movement away , or source "from/to". |

| Locative (LOC) | -t | indicates the indirect object of the clause, or spatial (place), or temporal (time). |

| Benefactive (BEN) | -lla | indicates that the referent of the noun benefits from the situation expressed by the clause. |

| Instrumental (INSTR) | -e | indicates that the referent of the noun is the instrument or by means which the subject of the clause achieves an action. |

| Examples with case marking | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Suffixes | Singular | Plural | Usage | |

| Nouns ending in a vowel | Nouns ending in a consonant | All Nouns | |||

| ABS | unmarked | fuwa "child" | gór "house" | manuš okkol "men/people" | Subject of intransitive clauses, indefinite and/or inanimate object |

| ERG | -e | fuwaye | bafe | manuš okkole | Subject of transitive clause |

| GEN | -r | fuwar | gór(o)r | - okkol(o)r | possessor of an NP |

| DAT | -re | fuware | gór(o)re | - okkol(o)re | Indirect Object |

| ABL | -ttu | fuwattu | gór(o)ttu | - okkol(o)ttu | recipient, movement away from, possessor in a possessive predicate |

| LOC | -t | bisanat "in bed" | gór(o)t | - okkol(o)t | spatial (in, at), movement toward (to) |

| BEN | -lla | fuwalla | gór(o)lla | - okkol(o)lla | oblique, for, intended for |

| INSTR | -e | gariye "by car" | - | gari okkole "by cars" | oblique, expresses the means of accomplishment |

In example (36) Salim in the Absolutive case , which is unmarked in Rohingya, and functions as the Subject of this intransitive clause (underlined).

| (36) | Role of ABS as Subject in an intransitive clause | |

| S | V | |

| Salim | boišše. | |

| Salim (ABS) | sat down. | |

| "Salim sat down." | ||

In example (37) the noun bat “rice” is marked (shown as underlined) by the Absolutive case marker, which is the bare form of the noun and is the direct object in this clause.

| (37) | Role of ABS as Direct Object in a transitive clause | ||

| S | O | V | |

| Salime | bat | hail. | |

| Salim (ERG) | rice (ABS). | ate. | |

| "Salim ate rice." | |||

In the following example, Salim is marked by Ergative marker, /-e/ and is the Subject in this transitive clause.

| (38) | Role of ERG as Subject in a transitive clause | ||

| S | O | V | |

| Salime | kitabwa | fore. | |

| Salim (ERG) | book (NC1.DEF.ABS). | read. | |

| "Salim read the book." | |||

In example (39), Moriyam is marked by the Genitive case marker /-r/ and is the Possessor of the Noun Phrase Moriyamor bái “Moriyam’s brother.”

| (39) | Role of GEN as Possessor in an NP | |||

| Possessor | S | Ind.Obj | V | |

| Moriyamor | báiye | hitare | maijjil. | |

| Moriyam (GEN) | brother (ERG). | him (DAT) | hit | |

| "Moriyam's brother hit him." | ||||

In example (40) the noun bouwore is marked by the Dative marker /-re/ and functions as the Indirect Object in the clause.

| (40) | Role of DAT as Indirect Object in a transitive clause | ||||

| S | Possessor | Ind.Obj | O | V | |

| Hasone | hitar | bouwore | fúl | dil. | |

| Hason (GEN) | his (GEN) | wife (DAT) | flower (ABS) | gave | |

| "Hasson gave flower to his wife." | |||||

In Rohingya, the case markers for Locative, Benefactive, Instrumental and sometimes Ablative case serve the same function as prepositions in English. Their function in the clause is more semantic than syntactic, expressing meanings such as source (ABL), location (LOC) and benefit (BEN). In example (41), the noun šohorottu is marked by Ablative marker /-ttu/, functioning in an oblique role in the clause.

| (41) | Role of ABL as Oblique in a clause | |||

| S | Oblique Object | V | ||

| Anware | ekkan | šohorottu | aišše. | |

| Anwar (ERG) | a (NC2.INDEF) | city (ABL) | came | |

| "Anwar came from a city." | ||||

In Rohingya, there are also a certain type of verbs that require their Subject in the Ablative case. We can call these verbs, “feeling/having” verbs. Consider the following examples:

| (42) | Role of ABL as Subject of "feeling/having" verbs | |||

| S | O | V | ||

| Hasonottu | sair | boin | ase. | |

| Hason(ABL) | four | sister | ||

| "Hason has four sisters." | ||||

| (43) | Role of ABL as Subject of "feeling/having" verbs | ||

| S | v | ||

| Ãttu | ḍor | lage. | |

| To me (ABL) | fear | feel | |

| "I am afraid/ I feel afraid." | |||

In example (44), the noun zagat “to/at place” is marked by the Locative marker /-t/ to denote the meaning of “to place.”

| (44) | Role of LOC as Oblique in a clause | ||||

| S | Oblique | V | |||

| Ãi | ek | zagattu | zagat | giyi. | |

| I (ERG) | NUM | place (ABL) | place (LOC) | went | |

| "I went from place to place." | |||||

In example (45), the noun maštorolla is the beneficiary of the action and is marked by the Benefactive marker /-lla/.

| (45) | Role of BEN as Oblique in a clause | |||

| S | Oblique | V | ||

| Ãra | maštorolla | ham | goriyum. | |

| We(ERG) | for teacher (BEN) | will work do | ||

| "We will work for teacher." | ||||

In example (46), the Instrumental case marker /-e/ on the noun gariye “by a car” expresses the means by which the action of arriving was achieved in this clause.

| (46) | Role of INSTR as Oblique in a clause | |||

| S | Oblique | V | ||

| Ãra | heṛe | gariye | aišši. | |

| We(ERG) | here | by car (INSTR) | came | |

| "We came here by car." | ||||

Modifying the Noun Phrase

Sometimes one needs to add more information to the noun to express a thought or idea more clearly. In Rohingya, a lot of things can be added to the noun, we call the result a noun phrase. The additional information we put in the phrase are called modifiers, which can be adjectives (ADJ), demonstratives (DEM), quantifiers (QUANT), and numerals (NUM). If words are added to a noun in a noun phrase, then we call the noun the head noun of the noun phrase.

Adjectives

There are words that express qualities, such as size ḍõr “big”, ‘sõṛo “small,” shape leṛa “thin”, values bala, gom “good” horaf “bad”, physical characteristics doro “strong” norom “soft”, “šundor “beautiful”, human characteristics, such as kuši “happy”, salak “wise,” and so on. These types of words are called “adjectives.” They can be added to a noun phrase to describe a head noun. They provide information on the quality of the noun. In Rohingya, adjectives occur before the head noun in an NP. Consider the following examples:

| (47) | ADJ | HEAD |

| furan | ṭebil | |

| old | table | |

| "old table" | ||

| (48) | ADJ | HEAD |

| hoišša | baf | |

| young | father | |

| "young father" | ||

| (49) | ADJ | HEAD |

| horaf | manuš | |

| bad | man | |

| "bad man" | ||

Note that if an adjective comes after the head noun, then it is an Attributive clause. Example (50) describes an NP, in which the head noun gór “house” is modified by an adjective ḍõr “big,” whereas example (51) shows an Attributive clause (complete clause/sentence), which consists of an NP and an ATP (Attributive Phrase) to make up a complete sentence.

| (50) | ADJ | HEAD |

| ḍõr | gór | |

| big | house | |

| "big house" | ||

| (51) | NP | ATP |

| Górgan | ḍõr. | |

| house | big | |

| "The house (is) big." | ||

Demonstratives

Demonstratives are words that can also be added to a noun, to help the speaker to show something; they identify more clearly what the speaker refers to, as in this, that, these, and those. It is important to distinguish between demonstrative adjectives and demonstrative pronouns. Demonstrative adjectives occur as modifiers in an NP, to say something about the distance reference of nouns, as in “this big house.” Demonstrative pronouns, on the other hand, occur in place of an NP, as in “This is a big house.” We can distinguish between near demonstratives and distant (far) demonstratives, as shown in the following table for Rohingya demonstratives.

| DEM | Near | Far |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | ei | he |

| Plural | ei | oi |

Near demonstratives

Near demonstratives define a noun as near to the speaker. The examples (52) and (53) describe the noun gór “house” with the usage of demonstrative adjective ei “this/these” as being near to the speaker. Note that Rohingya does not distinguish between singular and plural near demonstratives.

| (52) | ei | šõṛo | górgan |

| this | small | house | |

| "this small house" | |||

| (53) | ei | šõṛo | górgun |

| these | small | houses | |

| "these small houses" | |||

Distant demonstratives

Distant demonstratives define a noun as far from the speaker. The examples (54) and (55) describe the noun gór “house” with the usage of demonstrative adjectives he “that” oi “those” respectively as being distant from the speaker. Note that distant demonstratives are marked for plurality.

| (54) | he | šõṛo | górgan |

| that | small | house | |

| "that small house" | |||

| (55) | oi | šõṛo | górgun |

| those | small | houses | |

| "those small houses" | |||

Unlike English, which uses this, that, these, and those for both demonstrative adjectives and demonstrative pronouns, Rohingya demonstrative pronouns are distinct from demonstrative adjectives.

Quantifiers

There are two types of words that express the quantity of a noun. Words, such as, “many, all, several, some, few, are called quantifiers (QUANT). Words, which include numbers, such as “one, two, three, etc” are called numerals (NUM). All of these can modify an NP. In Rohingya, quantifiers occur before the head in the NP, as in examples (56) and (57). It is also optional to mark the head noun in plural, as in examples (56) and (57), in which head nouns din and mas are not marked for plurality, whereas in example (58), the head noun manuš “man” takes the plural marker okkol. Both constructions are considered correct and natural in Rohingya.

| (56) | QUANT | HEAD |

| bout | din | |

| many | day | |

| "many days" | ||

| (57) | QUANT | HEAD |

| beši | mas | |

| many | fish | |

| "many fish" | ||

| (58) | DEM | QUANT | HEAD | |

| ei | šob | manuš | okkol | |

| these | all | man | PL | |

| "all these people" | ||||

When some quantifiers, such as beggun “all, everyone” follow personal pronouns and demonstrative pronouns, they function as the co-head in the NP. As the head receive the case marker for the Noun phrase. Consider the following examples:

| (59) | hitara | beggun |

| they | all | |

| "they all / all of them" | ||

| (60) | tũwara | beggunore |

| you (PL) | all (DAT) | |

| "all of you (DAT)" | ||

| (61) | Ãra | beggun | hitar | fuwain. |

| We (PL) | all | his (GEN) | children | |

| "We all are his children." | ||||

| (62) | Iin | beggun | hitar | oibo. |

| these | all | his (GEN) | will become | |

| "All these will be his." | ||||

Numerals

The other type of words that express the quantity of a noun in an NP are numerals. In Rohingya, numerals occur before their head nouns. They also receive a noun classifier suffix, reflecting their head nouns. This is illustrated by the numeral dui “two” in examples (63)-(65), which receives different classifier suffixes, according to the noun class of the head. Note that when a noun is numbered in Rohingya, it is optional for the noun to receive the plural marker okkol, as described in the following examples.

| (63) | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| duiyan | šõṛo | gór | |

| two (NC2) | small | house | |

| "two small house(s)" | |||

| (64) | NUM | HEAD |

| duizon | manuš | |

| two (NC1) | man | |

| "two men" | ||

| (65) | NUM | ADJ | HEAD |

| duwa | ḍõr | mas | |

| two (NC1) | big | fish | |

| "two big fish" | |||

Cardinal numbers

Cardinal numbers are numerals that are used to count nouns, as in “two men, three chairs.” See examples (63)-(65). As mentioned earlier, when numerals modify an NP, they must reflect the class of the head noun. Consider the following table:

| Numbers with corresponding noun classifiers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bare form | NC1 | NC2 | Gloss | |

| ek | ekzon | uggwa | ekkan | "one" |

| dui | duizon | duwa | duiyan | "two" |

| tin | tinzon | tinnwa | tinnan | "three" |

| sair | sairzon | sairgwa | sairgan | "four" |

| fãz | fãzzon | fãzzwa | fãzzan | "five" |

| so | sozon | sowa | sowan | "six" |

| hãt | hãtzon | hãttwa | hãttan | "seven" |

| ašṭo | ãšṭozon | ãšṭowa | ãšṭowan | "eight" |

| no | nozon | nowa | nowan | "nine" |

| doš | došzon | doššwa | doššan | "ten" |

| egaro | egarozon | egarowa | egarowan | "eleven" |

| baro | barozon | barowa | barowan | "twelve" |

| tero | terozon | terowa | terowan | "thirteen" |

| soiddo | soiddozon | soiddowa | soiddowan | "fourteen" |

| funro | funrozon | funrowa | funrowan | "fifteen" |

| šullo | šullozon | šullowa | šullowan | "sixteen" |

| hõtoro | hõtorozon | hõtorowa | hõtorowan | "seventeen" |

| aṛoro | aṛorozon | aṛorowa | aṛorowan | "eighteen" |

| unnuš | unnušzon | unnuššwa | unnuššan | "nineteen" |

| kuri | kurizon | kuriwa | kuriwan | "twenty" |

| ekuri ek | ekuri ekzon | ekuri uggwa | ekuri ekkan | "twenty one" |

| ekuri dui | ekuri duizon | ekuri duwa | ekuri duiyan | "twenty two" |

| ekuri doš / tiriš (Bangla origin) | ekuri došzon | ekuri doššwa | ekuri doššan | "thirty" |

| ekuri egaro / tiriš ek | ekuri egarozon | ekuri egarowa | ekuri egarowan | "thirty one" |

| ekuri baro / tiriš dui | ekuri barozon | ekuri barowa | ekuri barowan | "thirty two" |

| duikuri / sališ | duikurizon | duikuriwa | duikuriwan | "forty" |

| duikuri ek / sališ ek | duikuri ekzon | duikuri uggwa | duikuri ekkan | "forty one" |

| duikuri dui / sališ dui | duikuri duizon | duikuri duwa | duikuri duiyan | "forty two" |

| duikuri doš / fonzaiš | duikuri došzon | duikuri doššwa | duikui doššan | "fifty" |

| duikuri egaro / fonzaiš ek | duikuri egarozon | duikuri egarowa | duikuri egarowan | "fifty one" |

| duikuri baro / fonzaiš dui | duikuri barozon | duikuri barowa | duikuri barowan | "fifty two" |

| tinkuri / haiṭ | tinkurizon | tinkuriwa | tinkuriwan | "sixty" |

| tinkuri ek / haiṭ ek | tinkuri ekzon | tinkuri uggwa | tinkuri ekkan | "sixty one" |

| tinkuri dui / haiṭ dui | tinkuri duizon | tinkuri duwa | tinkuri duiyan | "sixty two" |

| tinkuri doš / hoittor | tinkuri došzon | tinkuri doššwa | tinkuri doššan | "seventy" |

| tinkuri egaro / hoittor ek | tinkuri egarozon | tinkuri egarowa | tinkuri egarowan | "seventy one" |

| tinkuri baro / hoittor dui | tinkuri barozon | tinkuri barowa | tinkuri barowan | "seventy two" |

| sairkuri / aši | sairkurizon | sairkuriwa | sairkuriwan | "eighty" |

| sairkuri ek / aši ek | sairkuri ekzon | sairkuri uggwa | sairkuri ekkan | "eighty one" |

| sairkuri dui / aši dui | sairkuri duizon | sairkuri duwa | sairkuri duiyan | "eighty two" |

| suirkuri doš / nobboi | suirkuri došzon | sairkuri doššwa | sairkuri doššan | "ninety" |

| sairkuri egaro / nobboi ek | sairkuri egarozon | sairkuri egarowa | sairkuri egorawan | "ninety one" |

| sairkuri baro / nobboi dui | sairkuri barozon | sairkuri barowa | sairkuri barowan | "ninety two" |

| ekšot | ekšotzon | ekšottwa | ekšottan | "one hundred" |

| ekšot ek | ekšot ekzon | ekšot uggwa | ekšot ekkan | "one hundred and one" |

| duišot | duišotzon | duišottwa | duišottan | "two hundred" |

| ekhazar | ekhazarzon | ekhazargwa | ekhazargan | "one thousand" |

Ordinal numbers

Ordinal numbers tell you the order of things, like the first, the second, the third and so on. There is no clear pattern as to how ordinal numbers are formed for the first three numbers, however, for the rest ordinal numbers are formed by the use of the word lombor, which means “number” in Rohingya, as illustrated by the following table. As modifiers in the NP, they occur after their head noun, as shown in examples (66) – (68).

| Ordinal numbers | Gloss |

|---|---|

| foila | "first" |

| dusora | "second" |

| tisera | "third" |

| sair lombor | "fourth" |

| fãz lombor | "fifth" |

| so lombor | "sixth" |

| hãt lombor | "seventh" |

| ašṭo lombor | "eighth" |

| no lombor | "ninth" |

| doš lombor | "tenth" |

| (66) | foila | din |

| first | day | |

| "first day" | ||

| (67) | tisera | bosor |

| third | year | |

| "third year" | ||

| (68) | fãz lomboror | ṭebil |

| five number's | table | |

| "fifth table" | ||

Pronouns and Possessives

In some cases a noun phrase may look different from the ones we have seen so far. Instead of showing a prototypical noun, they may be replaced by just a pronoun.

Pronouns are words that take the position of nouns. The meaning of a pronoun can only be determined by looking at the context. The different kinds of pronouns we find in Rohingya are; personal pronouns, such as “I, you, he, she, we, they”, demonstrative pronouns, such as “this, that, they”, and relative pronouns, such as “who, which.”

Personal pronouns

Personal pronouns are words that refer to people. They can stand alone, functioning as a noun phrase in a clause. The speaker is called the 1st person “I, we”, the person spoken to is called the 2nd person “you (SG)and (PL)”, and the person spoken about is called the 3rd person “he, she, they”. In Rohingya, pronouns have five morphologically distinct cases, which are used in the following way in terms of their syntactic function in the clause:

| Cases | Case markers | Syntactic function in the clause | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ergative (ERG) | -e (sometimes bare form) | Aka. Subject pronoun, which indicates the subject of the clause. | ãi "I" |

| Genitive (GEN) | -r | Aka. Possessive pronoun, which indicates possession. The possessor is in the Genitive case and is expressed by the suffix "-r". | ãr "my / mine" |

| Dative (DAT) | -re | Aka. Object pronoun , which indicates the direct or indirect object of the clause, expressed by the suffix "-re". | ãre "me" |

| Ablative (ABL) | -ttu | indicates the subject of the clause, when used with certain verbs, such as "to feel," "to have," and is expressed by the suffix "-ttu". | ãttu "to me" |

| Benefactive (BEN) | -e | Aka. Oblique object pronoun, which indicates that the referent of the pronoun benefits from the situation expressed by the clause, and is marked by the suffix "-lla". | ãlla "for me". |

| Personal pronouns in Rohingya | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Ergative | Genitive -r | Dative -re | Ablative -ttu | Benefactive -lla |

|

| 1st person | ãi | ãr | ãre | ãttu | ãlla | |

| 2nd person | non-honorific | tui | tor | tore | tottu | tolla |

| honorific | tũi | tũwar | tũware | tũwattu | tũwalla | |

| 3rd person | masc. | hite | hitar | hitare | hitattu | hitalla |

| fem. | hiba | hibar | hibare | hibattu | hiballa | |

| Plural | ||||||

| 1st person | ãra | ãrar | ãrare | ãrattu | ãralla | |

| 2nd person | tũwara | tũwarar | tũwarare | tũwarattu | tũwaralla | |

| 3rd person | hitara | hitarar | hitarare | hitarattu | hitaralla | |

Here are some examples of the 1st person PL “we” (underlined), in different functions in different clauses:

| (69) | Subject | VP |

| Ãra | buzi. | |

| we (ERG) | understand | |

| "We understand." | ||

| (70) | Possessive pronoun | |||

| Ãrar | sati | beši | bala. | |

| our (GEN) | umbrella | very | good | |

| "Our umbrella (is) very good." | ||||

| (71) | Subject | Object | Verb |

| Hitara | ãrare | dekkil. | |

| they (ERG) | us (DAT) | see (PAST) | |

| "They saw us." | |||

| (72) | Subject | Object | Verb |

| Ãrattu | fuwain | ase. | |

| to us (ABL) | children (ABS) | have | |

| "We have children." | |||

| (73) | Subject | Verb | |

| Ãrattu | oran | lager. | |

| to us (ABL) | tired | feel | |

| "We feel tired / we are tired." | |||

| (74) | Subject | Oblique Object | Object | Verb | ||

| Hitara | ãralla | hana | dana | bebosta | goijjil. | |

| they (ERG) | for us (BEN) | food | seed (ABS) | preparation | do | |

| "They prepared food for us." | ||||||

Demonstrative pronouns

We have, earlier, looked at demonstrative adjectives. We stated that demonstrative adjectives describe the head noun in the NP, that is, they modify the head noun, saying something about the distance reference of the noun, whether the object is near or far. Examples (75) and (76) are examples of NPs with demonstrative adjectives modifying the head noun. They are not complete sentences.

| (75) | DEM.ADJ | NP |

| ei | fiyalawa | |

| this | cup (NC1.DEF) | |

| "this cup" | ||

| (76) | DEM.ADJ | NP |

| he | fiyalawa | |

| that | cup (NC1.DEF) | |

| "that cup" | ||

| (77) | DEM.PRON | ||

| Iba | uggwa | fiyala. | |

| this | a (NC1.INDEF) | cup | |

| "This is a cup." | |||

| (78) | DEM.PRON | ||

| Hiba | uggwa | fiyala. | |

| that | a (NC1.INDEF) | cup | |

| "That is a cup." | |||

Now, compare examples (75) and (76) with examples (77) and (78). Note that ei fiyalawa “this cup” and he fiyalawa “that cup” are incomplete sentences, where as Iba uggwa fiyala “This is a cup” and Hiba uggwa fiyala “That is a cup” are complete thoughts or sentences. The demonstratives iba and hiba used in examples (77)and (78) are called demonstratives pronouns. As pronouns they occur in place of an NP.

| Classifiers | Near | Far | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SG | NC1 | iba "this" | hiba "that" |

| SG | NC2 | iyan "this" | hiyan "that" |

| PL | iin "these" | uin "those" |

As an NP they must reflect the class of the noun they refer to in the clause when they occur in the singular, as in the following examples:

| (79) | DEM.PRON with NC1 | ||

| Iba | uggwa | fúl. | |

| this (NC1) | a (NC1.INDEF) | flower | |

| "This is a flower." | |||

| (80) | DEM.PRON with NC2 | ||

| Iyan | ekkan | gór. | |

| this (NC2) | a (NC2.INDEF) | house | |

| "This is a house." | |||

| (81) | DEM.PRON with NC1 | ||

| Hiba | uggwa | sep. | |

| that (NC1) | an (NC1.INDEF) | apple | |

| "That is an apple." | |||

| (82) | DEM.PRON with NC2 | ||

| Hiyan | ekkan | hal. | |

| that (NC2) | a (NC2.INDEF) | river | |

| "That is a river." | |||

When they occur in the plural, there is no distinction between the two noun classes. In other words, regardless of which noun they refer to in the clause, the demonstrative pronouns in the plural remain the same, as illustrated by the examples (83)-(86).

| (83) | DEM.PRON in PL | ||

| Iin | bilai | okkol. | |

| these (PL) | cat (NC1) | PL | |

| "These are cats." | |||

| (84) | DEM.PRON in PL | ||

| Iin | ṭebil | okkol. | |

| these (PL) | table (NC2) | PL | |

| "These are tables." | |||

| (85) | DEM.PRON in PL | ||

| Uin | holom | okkol. | |

| those (PL) | pen (NC1) | PL | |

| "Those are pens." | |||

| (86) | DEM.PRON in PL | ||

| Uin | doroza | okkol. | |

| those (PL) | door (NC2) | PL | |

| "Those are doors." | |||

Like personal pronouns, demonstrative pronouns also receive case markers in Rohingya, as illustrated by the following table.

| Demonstrative pronouns with case inflection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Classifier | Bareform | Genitive -r | Dative -re | Ablative -ttu | Locative -t | Benefactive -lla |

| Near | NC1 | iba | ibar | ibare | ibattu | iballa | |

| NC2 | iyan | iyanor | iyanore | iyanottu | iyanot | iyanolla | |

| Far | NC1 | hiba | hibar | hibare | hibattu | hiballa | |

| NC2 | hiyan | hiyanor | hiyanore | hiyanottu | hiyanot | hiyanolla | |

| Plural | |||||||

| Near | iin | iinor | iinore | iinottu | iinot | iinolla | |

| Far | uin | uinor | uinore | uinottu | uinot | uinolla | |

Relative pronouns

A relative pronoun (RELP) is a pronoun that marks or introduces a relative clause. The function of relative clause is to say something more about the noun in the clause. The Rohingya relative pronoun ze “who/that” is inflected for both number and case and introduces a relative clause. The chart below shows both singular and plural forms of ze “who/that” with case inflection.

| Relative pronouns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ergative -e | Genitive -r | Dative -re | Ablative -ttu | Benefactive -lla |

|

| Singular | ze, zibaye | zar, zibar | zare, zibare | zattu, zibattu | zalla, ziballa |

| Plural | zara | zarar | zarare | zarattu | zaralla |

Example (87) illustrates a simple transitive clause, in which Hamid is the Subject of the verb ador gore “loves” and the Object is beṛire “woman” marked by the Dative case. Example (88) illustrates the same clause, functioning now as a relative clause modifying the noun beṛi “woman.”

| (87) | Main clause | |||

| Hamide | ekzon | beṛire | ador gore. | |

| Hamid (ERG) | a (NC1.INDEF) | woman (DAT) | love | |

| "Hamid loves a woman." | ||||

| (88) | Relative pronoun | Relative clause | Main clause | |

| Ze | beṛire | Hamide | ador gore | |

| RELP | woman (DAT) | Hamid (ERG) | love do | |

| "the woman that Hamid loves" | ||||

A more in-depth analysis of Rohingya Relative pronouns and their function in the various types of Relative clauses will be provided in the upcoming grammatical description of the Rohingya language.

Possessives

In Rohingya both nouns and pronouns can express possession or ownership, e.g., “This cup is father’s,” or “The shoes are mine.” Possessor is marked by the Genitive case marker /-r/, which is directly attached to the noun, as described by the examples (89)-(90).

| (89) | Fúllwa | mar. |

| flower (NC1.DEF) | mother's (GEN) | |

| "The flower (is) mother's." | ||

| (90) | Holommwa | maštoror. |

| pen (NC1.DEF) | teacher's (GEN) | |

| "The pen (is) teacher's." | ||

As mentioned earlier, pronouns can also show that something belongs to someone, as in “These shoes are mine,” to avoid repeating the same word. These types of pronouns are called Possessive pronouns. Possessives in Rohingya are expressed by using the Genitive case marker on pronouns.

| Personal pronouns in Rohingya | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Genitive -r | Gloss | |

| 1st person | ãr | "mine" | |

| 2nd person | non-honorific | tor | "yours" |

| honorific | tũwar | "yours" | |

| 3rd person | masc. | hitar | "his" |

| fem. | hibar | "hers" | |

| Plural | |||

| 1st person | ãrar | "ours" | |

| 2nd person | tũwarar | "yours" | |

| 3rd person | hitarar | "theirs" | |

Here are some examples of Possessive pronouns:

| (91) | Zutagun | ãr. |

| the shoes (NC2.DEF) | mine (GEN) | |

| "The shoes (are) mine." | ||

| (92) | He | ṭebilgan | tor. |

| that | table (NC2.DEF) | yours (SG.NHON) | |

| "That table (is) yours." | |||

| (92) | Ei | šundoijja | górgan | hitarar. |

| this | beautiful | house (NC2.DEF) | theirs (GEN) | |

| "This beautiful house (is) theirs." | ||||

Verbs

A word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, and forming the main part of the predicate of a sentence, such as hear, become, happen.

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com

Verbs are words that tell us what someone is doing, as in He runs everyday, what is happening or about a situation, as in He is here now. Every language has ways of expressing when an event or an action occurred, if it is still happening, if the event is complete, or how real or probable the event is. In Rohingya, these are expressed by different markers on the verbs. Here are some examples:

| Verb ha- "eat", inflected for tense | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (93) | Ãi | hai. | Simple present |

| I | eat | ||

| Ãi | hailam. | Simple past | |

| I | ate | ||

| Ãi | haiyum. | Simple future | |

| I | will eat | ||

| Ãi | hair. | Present progressive | |

| I | am eating | ||

| Ãi | haiyi. | Present perfect | |

| I | have eaten | ||

| Ãi | hailam. | Past perfect | |

| I | had eaten | ||

| Ãi | hat aššilam. | Past progressive | |

| I | was eating | ||

Tense

Tense–aspect–mood (commonly abbreviated tam) or tense–modality–aspect (abbreviated as tma) are a group of grammatical categories that covers the expression of tense (location in time), aspect (fabric of time – a single block of time, continuous flow of time, or repetitive occurrence), and mood or modality(degree of necessity, obligation, probability, ability).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki

In grammar, tense, aspect and modality (also mode or mood) are three different grammatical categories. However, for the readers of this basic grammar, we will treat them under one category, which we can call tense.

In Rohingya, tense is manifested by the use of specific markers on the verbs in their conjugation patterns. Let us now take a look at the following three examples. In the first example, /-i/ (underlined) in ham gori signals simple present tense. In the second example /-ir/ (underlined) in ham gorir signals present progressive tense, while in the last example /-ilam/ (underlined) in ham gorilam signals simple past tense.

- Ãra fotti din ham gori. “We workØ every day.”

- Ãra ehon ham gorir. “We are working now.”

- Ãra gota hailla ham gorilam. “We worked yesterday.”

The following table shows the complete conjugation pattern for the verb gor– “do” in the simple present tense. If we know the bare form of the verb, we can identify the specific forms that express tense. Consider example (94):

| (94) | Person | gor- "do" | Simple present tense markers | ||

| 1p | gor- | -i | gori | "(I / we) do" | |

| 2p (non-honorific) | gor- | -os | goros | "(you (NHON)) do" | |

| 2p (honorific) | gor- | -o | goro | "(you) do" | |

| 3p | gor- | -e | gore | "(he / she / they) do" |

In example (94) we see that the verb root is gor– and the suffixes /-i/, /-os/, /-o/ and /-e/ not only serve as tense markers (specifically simple present tense markers), but they also give additional information about the subject of the verb. This is also person agreement. It is obligatory for all verbs in Rohingya to have this person marker, which lets the hearer know what/who the Subject of that verb is. Let us look at another example:

| (95) | Person | lek- "write" | Simple present tense markers | ||

| 1p | lek- | -i | leki | "(I / we) write" | |

| 2p (non-honorific) | lek- | -os | lekos | "(you (NHON)) write" | |

| 2p (honorific) | lek- | -o | leko | "(you) write (SG/PL)" | |

| 3p | lek- | -e | leke | "(he / she / they) write" | |

In the examples above, we see that the suffix /-i/ agrees with ãi “I” and ãra “we”, /-os/ and /-o/ agree with tui “you (non-honorific)” and tũi / tũwara “you” (honorific) respectively, and /-e/ agrees with hiba “she,” hite “he,” and hitara “they.”

Present time

When we tell a story about the present, or something that usually happens, the present time becomes the main time in the story, and we use present tense system:

| Present perfect (before now) | ⟵ | Present (now) |

| Present progressive (right now) |

There are three types of present tense in Rohingya:

- Simple present(now), marked by the suffixes /-i/, /-o/ and /-e/ : is used for an action that is happening at the moment of speech, or also about actions that habitually take place.

- Present progressive (right now), marked by the suffixes /-ir/, /-or/ and /-er/: conveys an action that is ongoing in the present, as in “I’m running.”

- Present perfect (before now), marked by the suffixes /-iyi/, /-iyo/ and /-iye/: expresses an action which occurred before the time of speaking but has current relevance, as in “I have run.”

Simple Present

The simple present tense expresses actions that are happening at the same time as the sentence is spoken and also for actions that take place repeatedly. The following table shows the simple present tense forms of Rohingya verbs.

| Person (Subject) | Simple Present tense marker | Example gor- "do" | Example dũr- "run" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -i | gor-i | gori | dũr-i | dũri |

| PL | ãra | gor-i | gori | dũr-i | dũri | ||

| 2p | SG | tũi | -o | gor-o | goro | dũr-o | dũro |

| PL | tũwara | gor-o | goro | dũr-o | dũro | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -e | gor-e | gore | dũr-e | dũre |

| PL | hitara | gor-e | gore | dũr-e | dũre | ||

| Person (Subject) | Simple Present tense marker | Example za- "go" | Example ha- "eat" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -i | za-i | zai | ha-i | hai |

| PL | ãra | za-i | zai | ha-i | hai | ||

| 2p | SG | tũi | -o | za-o | zo1 | ha-o | ho |

| PL | tũwara | za-o | zo | ha-o | ho | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -e | za-e | za2 | ha-e | ha |

| PL | hitara | za-e | za | ha-e | ha | ||

NOTE 1: When a verb root ends with /a-/ and the following suffix starts with /-o/, the two vowels coalesce and become a single vowel /-o/, as vowel clusters, such as /-ao/ is not allowed in Rohingya syllable structures.

NOTE 2: Similarly, when a verb roots ends with /a-/ and the following suffix starts with /-e/ , the two vowels coalesce and become /-a/.

Here are some examples:

| (96) | Ãra | fotti | din | ham gori. |

| we | every | day | work do (PRES.1) | |

| "We work everyday." | ||||

| (97) | Hite | fotti | din | bat | ha. |

| he | every | day | rice | eats (PRES.3) | |

| "He eats rice everyday." | |||||

| (98) | Tũi | hameka | dũro. |

| you (HON) | always | run (PRES.2) | |

| "You always run." | |||

Present Progressive

Present progressive tense in Rohingya expresses an ongoing action and is formed by the use of the markers /-ir/ which agrees with ãi “I” and ãra “we”, /-or/ which agrees with tũi / tũwara “you,” and /-er/ which agrees with hiba “she,” hite “he,” and hitara“they,” as shown in the table below.

| Person (Subject) | Present Progressive marker | Example gor- "do" | Example dek- "see/look" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -ir | gor-ir | gorir | dek-ir | dekir |

| PL | ãra | gor-ir | gorir | dek-ir | dekir | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -or | gor-or | goror | dek-or | dekor |

| PL | tũwara | gor-or | goror | dek-or | dekor | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -er | gor-er | gorer | dek-er | deker |

| PL | hitara | gor-er | gorer | dek-er | deker | ||

| Person (Subject) | Present Progressive marker | Example ha- "eat" | Example za- "go" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -ir | ha-ir | hair | za-ir | zair |

| PL | ãra | ha-ir | hair | za-ir | zair | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -or | ha-or | hor1 | za-or | zor |

| PL | tũwara | ha-or | hor | za-or | zor | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -er | ha-er | har2 | za-er | zar |

| PL | hitara | ha-er | har | za-er | zar | ||

NOTE 1: When a verb root ends with /a-/ and the following suffix starts with /-o/, the two vowels coalesce and become a single vowel /-o/, as vowel clusters, such as /-ao/ is not allowed in Rohingya syllable structures.

NOTE 2: Similarly, when a verb roots ends with /a-/ and the following suffix starts with /-e/ , the two vowels coalesce and become /-a/.

Consider the following examples:

| (99) | Ãi | ehon | dũrir. |

| I | now | running (PPROG.1) | |

| "I'm running now." | |||

| (100) | Bafe | edde | Hassone | ehon | hana | har. |

| father (ERG) | now | Hasson (ERG) | now | food (ABS) | eating (PPROG.3) | |

| "Father and Hasson are eating food now." | ||||||

| (101) | Tũwara | ekkan | farat | zor. |

| you (PL) | a (NC2.INDEF) | village (LOC) | going (PPROG.2) | |

| "You are going to a village." | ||||

NOTE: PPROG stands for present progressive tense.

Present Perfect

In Rohingya, the present perfect aspect expresses an action which happened in the past, but with continuing relevance in the present and is formed by the markers /-iyi/ which agrees with ãi “I” and ãra “we”, /-iyo/ which agrees with tũi / tũwara “you,” and /-iye/ which agrees with hiba “she,” hite “he,” and hitara“they,” as described by the following table.

| Person (Subject) | Present perfect marker | Example gor- "do" | Example dek- "see/look" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -iyi | gor-iyi | goijji | dek-iyi | deikki |

| PL | ãra | gor-iyi | goijji | dek-iyi | deikki | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -iyo | gor-iyo | goijjo | dek-iyo | deikko |

| PL | tũwara | gor-iyo | goijjo | dek-iyo | deikko | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -iye | gor-iye | goijje | dek-iye | deikke |

| PL | hitara | gor-iye | goijje | dek-iye | deikke | ||

| Person (Subject) | Present perfect marker | Irregular verb za- "go" | Example o- "be/become" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -iyi | za-iyi | giyi | o-iyi | oiyi |

| PL | ãra | za-iyi | giyi | o-iyi | oiyi | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -iyo | za-iyo | giyo | o-iyo | oiyo |

| PL | tũwara | za-iyo | giyo | o-iyo | oiyo | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -iye | za-iye | giye | o-iye | oiye |

| PL | hitara | za-iye | giye | o-iye | oiye | ||

Here are some examples:

| (102) | Hite | aiye | ne? |

| he | has come (PPERF.3) | QP | |

| "Has he come?" | |||

NOTE: PPERF stands for present perfect tense. QP stands for question particle, a marker which signals that this is a question, not a statement.

| (103) | Before now | (104) | Now | |||

| Hite | aiye. | Hite | ehon | eṛe. | ||

| He | has come (PPERF.3) | has come (PPERF.3) | now | here | ||

| "He has come." | "He (is) here." | |||||

| (105) | Before now | (106) | Now | |||||

| Ãra | bat | haiyi. | Ãrattu | buk | lager | nai. | ||

| we | rice (ABS) | have eaten (PPERF.1) | to us (ABL) | hunger | feel | NEG | ||

| "We have eaten rice." | "We are not hungry now." | |||||||

NOTE: NEG stands for negation.

| (107) | Before now | (108) | Now | |||

| Hitara | giye. | Hitara | eṛe | nai. | ||

| they | have gone (PPERF.3) | they | here | NEG | ||

| "They have gone." | "They (are) not here now." | |||||

Past time

Coming soon!

Simple Future

Simple future tense is used to express actions that will happen after the time of utterance. The following table illustrates how Rohingya verbs are inflected for simple future tense.

| Person (Subject) | Simple Future tense marker | Example gor- "do" | Example ha- "eat" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -iyum | gor-iyum | goriyum1 | ha-iyum | haiyum |

| PL | ãra | gor-iyum | goriyum | ha-iyum | haiyum | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -iba | gor-iba | goriba | ha-iba | haiba |

| PL | tũwara | gor-iba | goriba | ha-iba | haiba | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -ibo | gor-ibo | goribo | ha-ibo | haibo |

| PL | hitara | gor-ibo | goribo | ha-ibo | haibo | ||

| Person (Subject) | Simple Future tense marker | Example za- "go" | Example o- "be" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p | SG | ãi | -iyum | za-iyum | zaiyum | o-iyum | oiyum |

| PL | ãra | za-iyum | zaiyum | o-iyum | oiyum | ||

| 2p | SG | tui, tũi | -iba | za-iba | zaiba | o-iba | oiba |

| PL | tũwara | za-iba | zaiba | o-iba | oiba | ||

| 3p | SG | hiba, hite | -ibo | za-ibo | zaibo | o-ibo | oibo |

| PL | hitara | za-ibo | zaibo | o-ibo | oibo | ||

| (109) | Ãi | ekzon | bala | baf | oiyum. |

| I | a (NC1.INDEF) | good | father | will (FUT.1) | |

| "I will be a good father." | |||||

| (110) | Hitara | hara | dũribo. |

| they | soon | will run (FUT.3) | |

| "They will run soon." | |||

| (111) | Tũi | ekzon | nas | oibo. |

| you (HON) | soon | nurse | will be (FUT.2) | |

| "You will be a nurse." | ||||

| (112) | Tũi | ekzon | nas | oibo. |

| you (HON) | a (NC1.INDEF) | nurse | will be (FUT.2) | |

| "You will be a nurse." | ||||

| (113) | Hibaye | uggwa | kitab | aijja | foribo. |

| she (ERG) | a (NC1.INDEF) | book (ABS) | today | will read (FUT.3) | |

| "She will read a book today." | |||||

Sentence mood

Coming soon!

Clause combining

Coming soon!